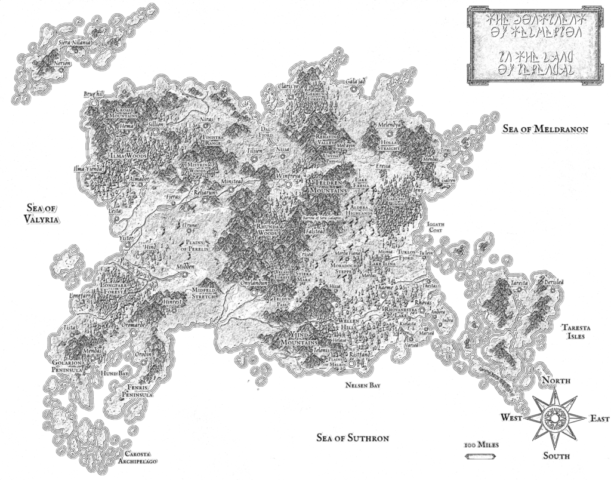

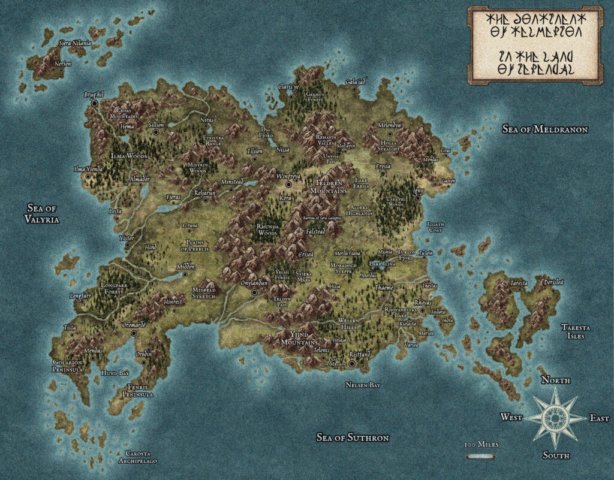

Dawnbringer is a series of novels set in the world of Ierendal, upon the small continent of Telmerion, cold and rugged and yet inhabited since the beginning of human history by the first family of humankind. Though the setting is high fantasy — a work of co-creative imagination fashioning a mythical world with its own history and geography — the plot and the ins-and-outs of the world are deeply realistic, portraying as it were an ancient and long-forgotten past of our own world. Or more precisely, what is offered here is a mythical exposition of the true past that we all share — with very little magic or other fantasy tropes, but with a great deal of “magic,” in other words, a world filled with wonders and terrors of all kinds, from the ancient guardians of the world, the Anaion, to vicious and deadly beasts such as dragons, eötenga, and druadach. The characters find themselves caught in the cosmic battle between light and darkness, between the weakness of love and the power of hate, which casts its rays and its shadows also into the heart of every man and woman. The journey marked out before their feet calls for integrity, fidelity, and heroism, and also something even more, something that lies at the heart of every good adventure and every life, and which is the very measure of man.

Explore the World of Ierendal and the Story of Dawnbringer:

Learn More:

Why fantasy?

I have explored these questions quite thoroughly in two chapters of the book Creating a Home for the Word, both chapters of which are also in audio form on YouTube, even if there is still more to explain. Quite simply, not only was fantasy an instrument of grace and a space of contemplation early in my life, but I believe that it is a form of storytelling with a particular depth and breadth (though sadly in our day it has been “cheapened” immeasurably).

High fantasy refers to the creation of a complete “secondary world” that exists in its own mythological consistency and believability, and presents itself as history, albeit mythic history. Low fantasy or contemporary fantasy rather introduces fantasy elements into persons or characters from the real world. Some examples of the first are The Lord of the Rings, or The Forgotten Realms (Dungeons and Dragons), or The Enduring Flame. Some examples of the second are Harry Potter, The Pendragon Cycle, and Dragons in Our Midst. The Chronicles of Narnia rides the line between the two, bringing real-life British children into a secondary world and back again (similarly with A Song for Albion or the works of George MacDonald).

But, without denying the beauty and rightness of the other forms of fantasy, high fantasy that is entirely consistent within itself, with no reference to this world, seems in my opinion to be the richest and most transparent reflection of myth. For it presents itself to us as “another world” that is nonetheless quite spontaneously understood to be this world, mythologically explored. And because of its own internal consistency, it allows the author to exercise their God-given nature as a co-creator or sub-creator who fashions in the likeness of the One who first made them, establishing the foundations of the earth and playing upon it always, delighting in the children of men (see Proverbs 8). In other words, in high fantasy the only “givens” are ontology and existential truth, that is, the nature of reality itself and the moral fabric of the universe: goodness, beauty, truth, and love. Everything else is freed from dependence on this-world prejudices and and paradigms, on mere historical facts, on our tendency to stop looking deeply at what we encounter each day, in order to teach us anew the “ethics of elfland,” the spirit of wonder and awe at the gift that everything is (to use G.K. Chesterton’s term). Yes, and this wonder before the gift is the foundation of all true philosophy, faith, and morality.

And so co-created stories, freeing us from the hum-drum everyday vision that so often imprisons us, are placed at the service of the revelation of this truth and love, this beautiful goodness, in the creation of a fictional world that nonetheless reflects and reveals the nature of the world that actually is, the world that through love God has created, and which through love a child of God has explored in storytelling. As W.H. Auden wonderfully said: “Present in every human being are two desires, a desire to know the truth about the primary world, the given world outside ourselves…and the other desire to make new secondary worlds of our own.”

How long is it?

The Dawnbringer series (or the “Complete Story” volume) is relatively short for the genre of epic high fantasy, and yet long enough to create an immersive world and narrative and, I hope, to sustain it throughout with richness and depth. The word counts are below (as a comparison, The Hobbit is 95,000 words, and the entire Lord of the Rings trilogy is 481,103, and the New Testament is about 180,000):

A Song for Niraniel: 95,188 words

A Song for Ristfand: 97,465 words

A Song for Eldaru: 90,417 words

A Song for Telmerion: 80,543 words

The entire story: 363,607 words

Will there be any other books?

God willing, absolutely. In fact I am currently writing a sequel to Dawnbringer taking place about thirty years after the events of the first “quartet.” While Dawnbringer stands entirely on its own as a self-enclosed story, and can be read independently with no loss, the sequel does hinge upon having read Dawnbringer first, if only to avoid some serious spoilers! I also hope to write more books in the legendarium as time passes, both carrying the story into the future as well as “fleshing out” the history of the world of Ierendal. A seed is already present within me about a full narrative of the central events of the 1st Age of Telmerion, for example.